Schools struggle to balance transgender protections, parental notification

For seven years, the New Hampshire School Boards Association had a model policy for how schools should treat transgender students and uphold their rights. And for years, many school boards in the state adopted the policy.

In February, that came to an end. As conservative criticism of LGBTQ+ school policies grew and the political rhetoric increased, the association removed its model policy. Instead, it advised districts to adopt policies as they see fit, and to consult legal counsel.

“The landscape was changing,” said Barrett Christina, executive director of the New Hampshire School Boards Association. “There are various court decisions; various state legislators have taken action one way or the other. We felt that withdrawing our model policy was prudent.”

The step back is part of a broader trend. As a lawsuit over Manchester School District’s transgender policies moves through the state courts, and as Republican state lawmakers advocate for legislation adding limits to teacher-student confidentiality, New Hampshire school boards are increasingly reversing course on some of their transgender student policies.

And now it’s been pulled into election season.

Politicians weighing in

On Sept. 29, Karoline Leavitt, the Republican nominee in the 1st Congressional District, held a press conference outside a Manchester school to criticize a former district policy that barred the disclosure of a student’s gender identity change to parents without the student’s consent.

“A policy like this is pitting good teachers against good parents,” Leavitt said. “And that should not be the role of the government. Teachers and parents should be working together to do what’s best for the child.”

State Republican lawmakers are also trying to pass a “parental bill of rights,” which would, in part, require schools to inform parents immediately after hearing that their child had given an update on their pronouns or gender expression. Gov. Chris Sununu, a Republican, opposed that bill last spring, threatening to veto it, but the measure is expected to return next year.

As the furor increases, school boards are listening. In March, just ahead of the lawsuit that was filed, the Manchester Board of School Committee stepped back from its policy, removing words that directly stated that parents should be left out of notification. Somersworth tightened its policy and required parental notification. Other school boards have hesitated and chosen not to bring forward additional policies centered on transgender students, advocates say.

To supporters of the parental rights movement, the policy backtracking is a welcome return to a system that prioritizes parental involvement.

But LGBTQ+ advocates say removing or watering down the policies can leave both teachers and gender nonconforming students with unclear guidelines. The upshot: Educators enter into decisions about whether to inform parents on a case-by-case basis.

“Some of the schools have become nervous, and I think they’ve made their policies in some ways more vague so that there’s less pushback,” said Jessica Goff, coordinator of community programming and engagement for Seacoast Outright, an LGTBQ+ advocacy organization. “So it’s not always clear what will happen in practice.”

Manchester lawsuit

The debate has played out most prominently in the state’s biggest school district.

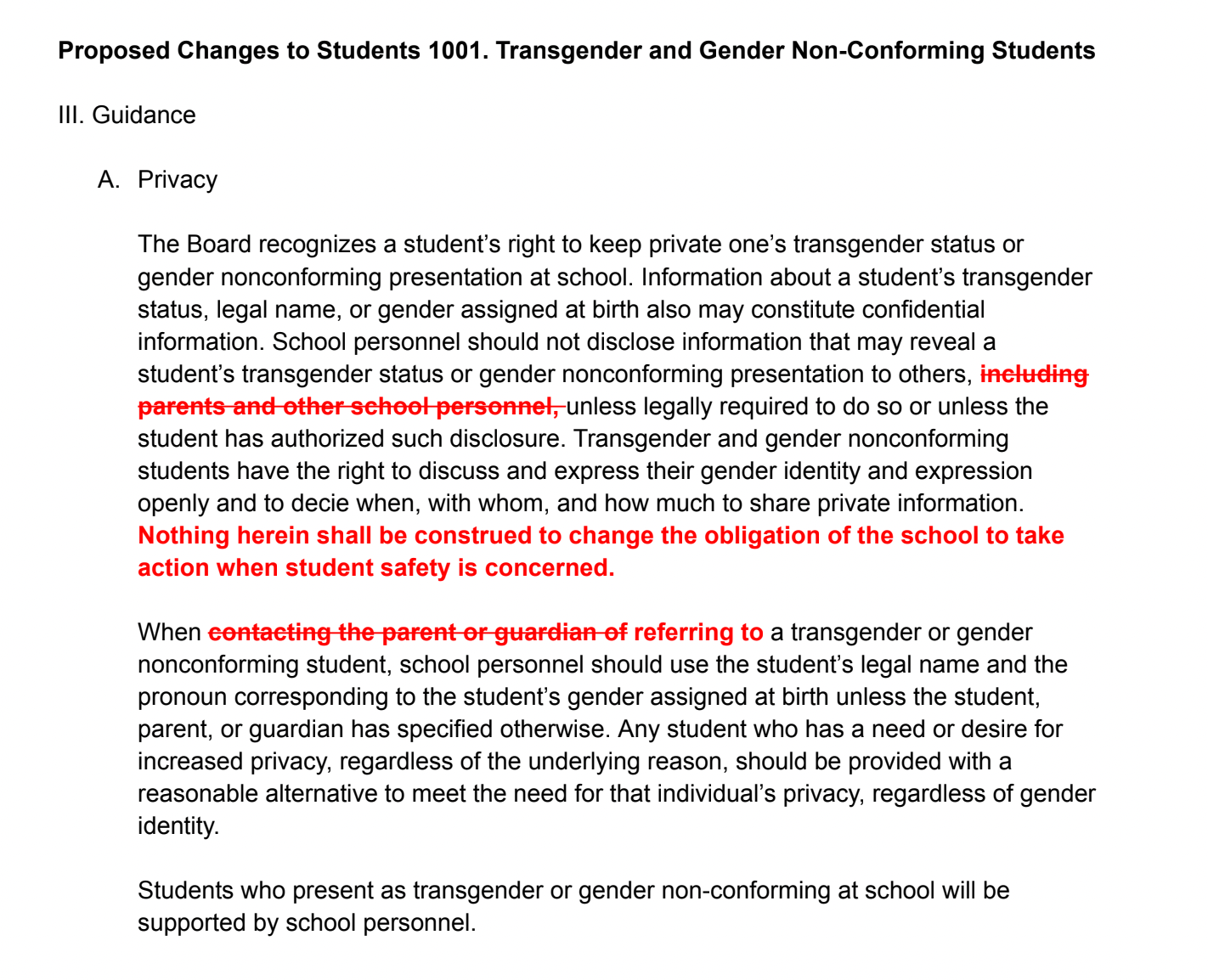

For a year, Manchester had a policy that barred teachers from disclosing a student’s “transgender status or gender nonconforming presentation” to anyone else, “including parents and other school personnel,” unless legally required to or authorized to do so by the student.

The policy also required educators to use a student’s legal name and pronouns assigned at birth when contacting a parent or guardian – even if the student was referred to differently at school – unless the student specified otherwise.

That policy, first added by the board in February 2021, changed this year. In March, a Manchester parent identified as “Jane Doe” filed a lawsuit over Manchester’s policy, represented by Rich Lehmann, an attorney who also serves as the New Hampshire Senate counsel. Doe said that the policy had prevented her from knowing her child wanted to be addressed by different pronouns in school, a request she opposed.

The lawsuit has been hit by a setback: Last month, Hillsborough County Superior Court dismissed it, a ruling that plaintiffs are planning to appeal to the state Supreme Court.

But even before the lawsuit was filed, the school board was already working to walk back some of the provisions. By March 14 of this year, the board had passed a revised policy: “School personnel should not disclose information that may reveal a student’s transgender status or gender nonconforming presentation to others unless legally required to do so or unless the student has authorized such disclosure.” The provision no longer specifies parents and other school personnel among those prohibited parties.

The new policy, which is now in place, says the legal name of the student should be used “when referring to” the student; it no longer says that must happen “when contacting the parent or guardian.”

In Somersworth, the school board updated its transgender student policy in May to require that parents give permission for any requests by their children to change their names or pronouns in the official school system. Before that change, the policy was less clear. On Tuesday, the board voted in a companion policy laying out a clear process for name changes and including parental permission.

The changes are meant to assuage concerns from parents and were not directly driven by the Manchester lawsuit, said Maggie Larson, the school board chairwoman, in an interview.

School administrators argue the changes don’t prevent a student from having confidential conversations with school counselors or other adults at school.

“Maybe a student is just looking for some support, some affirmation, that there’s somebody here that they can talk to, but maybe they know that they’re not going to make this publicly known for some time,” said Lori Lane, Somersworth superintendent, in an interview.

She added: “There’s been some concern that a child comes to a school counselor or a teacher or whoever in the school and that there’s this automatic phone call that gets made to parents. That is just not true.”

A divisive decision

The increasing unease faced by school board members over the political climate has affected state organizations, too.

First introduced in 2015, the New Hampshire School Boards Association’s sample policy featured a number of student safeguards districts could adopt. The template policy included right to privacy for a student who was transitioning but had not come out; a vow to avoid gender-segregated events; protections against harassment and discrimination; a protection of the right of a student to dress according to their gender identity; and a guarantee that students could participate in the sports team of their gender identity.

The policy had never been a recommendation, Christina clarified in an interview. The NHSBA has three categories of model policies it releases to school boards: those that are required by statute and must be implemented; those that are recommended but not required and should be adopted; and those that are optional and might be adopted. The template transgender policy fell into the latter category.

Still, the association did not feel comfortable continuing to distribute it this year even as an optional policy. The organization is now waiting for the outcome of the Manchester litigation at the state Supreme Court, as well as the “parental rights” bill in the State House next year.

“To the extent NHSBA reissues a revised sample policy, I think it would be based on what the Legislature does, and any legislation that comes out,” Christina said.

Some in the state disagree with that approach.

“I personally am disappointed that the school board association removed this policy from their books based on threats of legal action being taken in other districts,” said Karen Kharitonov, vice chairwoman of the Alton School Board, during a September school board meeting. “I think they did that hastily. I think they should have had some answers of how to replace it, how to revise it before just removing it.”

Kharitonov’s comments came as the Alton School Board was facing its own debate: whether to scrap its entire transgender policy, as one board member has recommended. That vote will be taken in November; most members appeared opposed to the idea.

Different visions forward

The escalating political fight has led to vastly different visions of where transgender school policies in New Hampshire should be heading.

LGBTQ+ activists say school boards are making a mistake by retreating from past policies, watering others down, and refraining from passing new policies. Doing so, they say, will leave transgender students vulnerable and deprive some of trusted adults to talk to. Passing more policy – and defending that policy – should be the path forward, some argue.

“Schools are awesome and teachers are trying their best, but if there’s no school policy to fall back on, sometimes the way that it’s implemented can vary based on the school and the teacher,” Goff said. “And I think you feel that inconsistency.”

A 2022 national survey by the Trevor Project, an LGBTQ+ advocacy organization, found that “fewer than 1 in 3 transgender and nonbinary youth found their home to be gender-affirming,” according to the organization. Of youth who reported to the survey that they had attempted suicide, 60 percent reported being in nonsupportive homes, the organization found.

But conservatives say any policy that shields parents from information about what’s happening with their child’s gender identity – even if that shield is requested by the student – is an infringement on the parents’ rights. That stance has found its way into debates, campaign stops, and vows of legislation. In May, the Republican-led House narrowly defeated House Bill 1431, after a handful of Republicans bucked their leadership. The bill would have required schools to notify parents about a range of changes to their student’s behavior, including discussions related to gender identity.

Next year, that legislation is returning, according to legislative service requests. It will be sponsored by current Republican Speaker Sherman Packard, a rare move for that position.

The debate hit new levels of emotion last month, when Democratic Party Chairman Ray Buckley expressed concern on Twitter that some transgender students who are outed to their parents by their schools “will be kicked out or beaten (to death) or commit suicide.”

But House Majority Leader Jason Osborne took immediate issue with the comments.

“Once again, New Hampshire Democrats prove that their entire party is out of touch with American and Granite State values,” Osborne said in an Oct. 4 statement. “… Now, in just the past week, their own party chair has dug in his heels on the fringe notion that schools should be withholding information from parents about their own children.”

For now, most school policies are vague or silent, advocates say. Absent broad victories from either side, most decisions are up to the teachers, students, and parents.

It’s a fine line to tread.

“Teachers certainly want to have very positive and collaborative relationships with their students,” Lane said. “But they also want to have them with parents.”

This story was produced by the editorially independent New Hampshire Bulletin, which is part of States Newsroom. Contact Editor Dana Wormald for questions: info@newhampshirebulletin.com. (The headline and subheads on this page have been modified by Granite Memo.)